As much as we’d all like to believe that our hearts look like the red ‘heart’ emoji, the heart is far more complex than that. To this day, we still don’t know everything there is to know about the heart. We do, however, have a vast knowledge of various existing heart diseases.

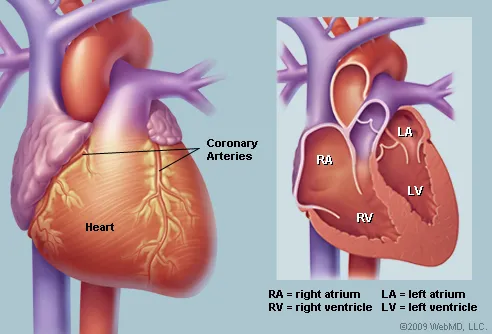

On the topic of heart complexity… Did you know that our heart has four chambers (enclosed spaces)? What about the fact that the heart connects to important blood vessels and veins? Or, that the heart sends blood out to our entire body?

Of course, there is so much more to know about the heart and how it functions. However, today we will take a closer look at the mechanism by which blood flows from a chamber of the heart (i.e., the right ventricle), through a large artery (i.e., the pulmonary artery), and to the lungs. Sometimes, this mechanism is disrupted, which may result in no symptoms or potentially fatal symptoms. We call this condition Pulmonary Stenosis (PS).

Let’s begin with some background on the pulmonary valve… Picture a door with three flaps that open and close to stop or allow for the flow of blood. This door is the pulmonary valve! The pulmonary valve sits between a chamber of the heart and the pulmonary artery. The blood from the pulmonary artery will travel to the lungs, pick up some oxygen, travel back to the heart, and get shipped off to the rest of the body.

Now back to PS… PS is responsible for 8-14% of heart defects at birth [5]. It most commonly occurs due to abnormalities in the development of the fetal heart during the first 9 weeks of pregnancy [4]. PS less commonly arises in adulthood, although it is still possible. There are four types of PS, the most common being vulvar stenosis, followed by branch stenosis, subvalvular stenosis, and supravalvar stenosis [1]. Simplified, stenosis refers to the narrowing of a passageway, and vulvar, branch, subvalvar, and supravalvar refer to the location of the narrowing. Sub- means ‘below’, supra- means ‘above’ and branch refers where the pulmonary artery breaks off into two branches – one for each lung.

PS is also associated with other heart defects at birth but, for the purpose of this post, we will focus on each type of PS as an individual occurrence. Vulvar stenosis is when the heart valve is thick or stiff and usually shaped like a dome with a narrow opening in the middle, unlike the normal three-flap-door [1]. Similarly, subvalvular stenosis is when there is a narrow opening below the valve, where supravalvular stenosis is a narrow opening above the valve. In the same way, branch stenosis is the narrowing of the branch(es) of the pulmonary artery that leads to the lungs.

Symptoms will vary depending on how narrow the area is. As you can imagine, the narrower the pulmonary artery, the harder it is for blood to pass through. This causes a lot of pressure and strain on the heart, which can eventually weaken the heart muscles [6]. Common symptoms include: a whooshing sound (i.e., murmur) heard with a stethoscope, fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, fainting, and a potential blue colour of the newborn [3]. For those with mild PS, the most common symptom is a whooshing sound, in which a doctor can identify in a routine check-up.

It is unclear exactly how or why PS occurs in the fetus during pregnancy. However, certain conditions can increase the risk of pulmonary valve stenosis. For example, if the mother has the German measles (rubella) during pregnancy, the baby is at higher risk of pulmonary valve stenosis [3]. Additionally, Noonan syndrome (a genetic disorder), Rheumatic fever (a complication of strep throat), and Carcinoid syndrome (a cancerous tumour) can increase the risk of damaged heart valves [3].

Many tests exist to identify all types of PS. Firstly, electrocardiograms allow healthcare professionals to identify abnormal heart pumping rhythms. Echocardiographs allow for the assessment and listening of the heart pumping. MRIs are useful to visualize the narrowing of the pulmonary artery and its branches. Multisite CTs allow for the visualization of the pulmonary artery, along with other components of the heart. Lastly, cardiac catherization and angiography is a method that identifies how much pressure there is in the heart. These tests allow for the identification of potential PS as well as its severity level in an individual. [1]

There are two main types of interventions for PS. Balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty is a method where a balloon physically pushes open the pulmonary valve. This method is most typically recommended and has a very low risk [1]. Additionally, in severe cases, individuals require surgery. During this procedure, the surgeon will cut open the flaps of the pulmonary valve (if fused together) or, as a last resort, remove some of the valve tissue to create a larger opening [1].

Individuals without any symptoms can have either wider or narrower openings. Those with wider openings usually need check ups every five years with an electrocardiogram and echocardiography [2]. For those with slightly narrower openings, the interval for such check ups decreases to 2-5 years [2]. When an individual has a very narrow opening, they will most likely need to undergo a balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty [2]. Individuals who present symptoms and have very narrow openings, will likely undergo a balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty. In severe cases, especially where pulmonary valvular stenosis overlaps other conditions (e.g., pulmonary subvalvular or supravalvular stenosis), surgical intervention is recommended [2].

Differences in the severity of PS also means differences in lifestyle changes! For example, those with mild PS have no exercise restrictions, those with moderate PS can only perform moderate exercises with no competitive or static (i.e., holding the same position) sports, and those with severe PS have many restrictions on physical activity, including those previously mentioned, and often require intervention before they can remove restrictions [1].

Importantly, PS requires you to maintain a long-term relationship with your doctor and cardiologist! Additionally, if a relative of yours has any type of PS, it’s a good idea to see your doctor for a check-up. You should also see a doctor if you present with any PS symptoms. Like I said, researchers don’t know exactly how PS occurs, however it’s likely to be party genetic, partly environmental, and partly the interaction between the two. Be aware, be educated, and keep your pulmonary artery happy and healthy!

Author: Mauda Karram

Cuypers, J.A.A.E., Witsenburg, M., van der Linde, D., Roos-Hesselink, J.W. (2013). Pulmonary stenosis: update on diagnosis and therapeutic options. Heart, 99(5), 339-347. http://dx.doi.org.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301964

2. Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560750/

Heaton, J., Kyriakopoulos, C. (2021). Pulmonic stenosis. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560750/

3. Source: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pulmonary-valve-stenosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20377034

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2021, August 26). Pulmonary valve stenosis. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pulmonary-valve-stenosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20377034.

4. Source: https://www.journals.ac.za/index.php/SAHJ/article/view/2903

Mitchell, B., & Mhlongo, N. (2018). The diagnosis and management of congenital pulmonary valve stenosis. SA Heart Journal, 15(1), 36-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24170/15-1-2903

5. Source: https://link-springer-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/article/10.1007/s00246-021-02545-w

Poupart, S., Navarro-Castellanos, I., Raboisson, M., Lapierre, C., Dery, J., Miro, J.,

Dahdah, N. (2021). Supravalvular and valvular pulmonary stenosis: predictive features and responsiveness to percutaneous dilation. Pediatric Cardiology, 42, 814-820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-021-02545-w

6. Source: https://heart.bmj.com/content/105/5/414

Ruckdeschel, E., & Kim, Y.Y. (2019). Pulmonary valve stenosis in the adult patient: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Heart, 105(5), 414-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312743

Leave a comment