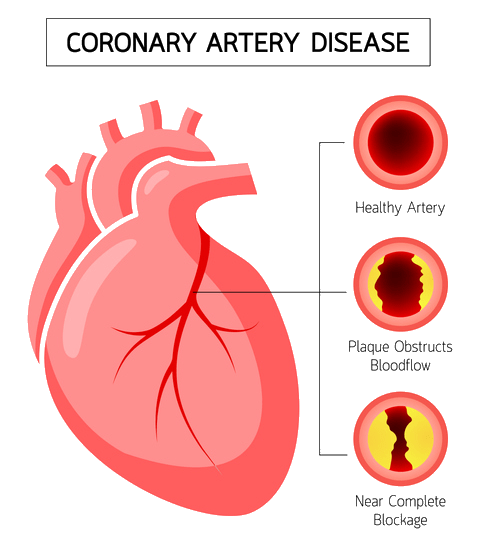

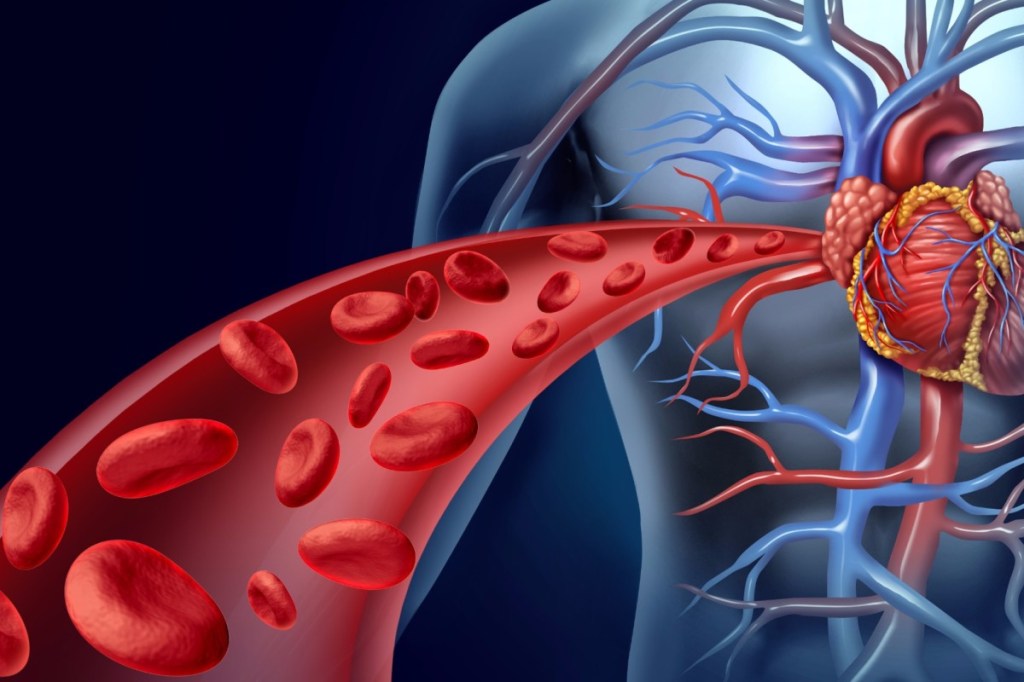

Currently, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the second leading cause of death in Canada. This heart disease is characterized by a buildup of plaque, a waxy-like substance, in the heart’s arteries. As the plaque accumulates, the arteries become narrower and eventually reach a point of partial or full blockage. This blockage will restrict the heart’s arteries from providing oxygen rich blood to the rest of the heart, potentially resulting in a heart attack, heart failure or death. Coronary heart disease is associated with many risk factors as well as preventative strategies.

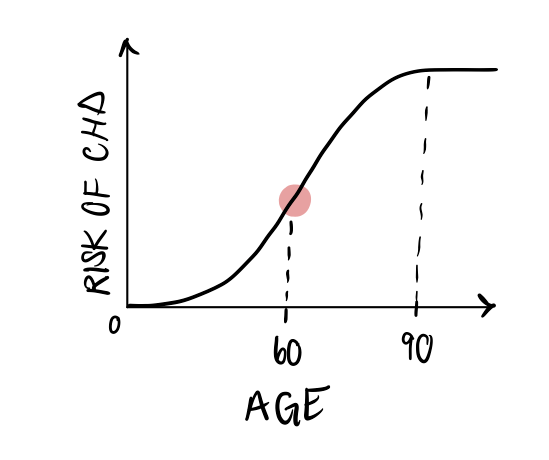

Since coronary heart disease incidence affects age groups differently, researchers sought out to calculate its lifetime risk. By doing so, researchers can estimate the risk of developing this disease during the individual’s remaining lifespan. Before the age of 40, they determined that the risk of developing CHD was incredibly low (1.2% in men, 0.2% in women). After the age of 40, the lifetime risk of CHD skyrocketed to 48.6% for men and 31.7% for women (4). Interestingly, every year free from coronary heart disease results in a decrease in the lifetime risk of a first CHD event (4). As individuals approach their 70s, the lifetime risk of CHD remains very high with 1/3 men and 1/4 women at risk. It seems that the risk of CHD increases with age, steeply rises after the age of 60 and flattens out after age 90. CHD incidence and risk also steeply increased for men in comparison to women. At all ages, men were more susceptible to coronary heart disease, conferring them a higher lifetime risk than women.

One risk factor of CHD is psychological stress. The most common type of stress studied and experienced is “stress at work”. According to a review including 197,473 participants, job strain significantly increased the risk of CHD incidence after a follow up of roughly 7.5 years later. The results also demonstrated that working over 55 hours a week in comparison to standard working hours (35-40 hours/week) contributed to the increased risk of CHD. Another important chronic stressor to consider is social isolation in adulthood (6). It was found that persistent social isolation and loneliness were associated with higher vulnerability to CHD. Furthermore, multiple studies also show a relationship between social economic status and CHD incidence. Low economic status in childhood and adulthood can give rise to many stressors in life, thus making these individuals more susceptible to coronary heart disease.

Another risk factor of CHD, that might surprise most, is depression. In fact, depression has been associated with increased CHD risk and death from cardiovascular diseases in over 100 studies. What’s eye popping from this literature are the biological and behavioural mechanisms in which depression contributes to increased risk of coronary heart disease. Regarding the biological mechanisms, depression alters an individual’s autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is the automatic portion of the human brain that controls heart rate, blood pressure and much more. Thus, depression elevates heart rate, causes abnormal heart-rate responses, and promotes many dysfunctions. These altered biological mechanisms are accompanied by behavioural mechanisms of depression. These include sedentary behaviour and a poor regulation of medication, diet, exercise, and smoking (1).

As mentioned above, maintaining unhealthy behaviours would significantly increase the risk of developing CHD. Thankfully, there are some solutions. Physical activity can independently decrease the risk of CHD. The American Heart Association and American College of Sports Medicine recommend 30 minutes of physical activity at a moderate intensity for 5 days a week, 20 minutes of aerobic exercise for 3 days/week and regular stretching and flexibility exercises for 2-3 days/week (5). This weekly routine will help prevent the CHD. To emphasize the importance of physical activity, clinical counseling is also critical for individuals at higher risk, specifically overweight individuals. Counselling interventions, such as health coaching, can better fit the unique needs of the individual’s body. Multiple studies have also identified a multi level approach for physical activity adherence which includes active individual participation, physician counselling and health coaching, community involvement and cardiac rehabilitation programs for patients needing further treatment. This multi-level approach is designed to tailor the needs of CHD patients looking to better their outcome and quality of life. Thus, not all is lost following a cardiac injury as cardiac rehabilitation is is a fast paced and new area of research.

Author: Jean Paul Sabat

References

(1) Carney, R. M., & Freedland, K. E. (2017). Depression and coronary heart disease. Nature reviews. Cardiology, 14(3), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.181

(2) Di Angelantonio, E., Thompson, A., Wensley, F., & Danesh, J. (2011). Coronary heart disease. IARC scientific publications, (163), 363–386.

(3) Khamis, R. Y., Ammari, T., & Mikhail, G. W. (2016). Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 102(14), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306463

(4) Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Larson, M. G., Beiser, A., & Levy, D. (1999). Lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease. Lancet (London, England), 353(9147), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10279-9

(5) Varghese, T., Schultz, W. M., McCue, A. A., Lambert, C. T., Sandesara, P. B., Eapen, D. J., Gordon, N. F., Franklin, B. A., & Sperling, L. S. (2016). Physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease: implications for the clinician. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 102(12), 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308773

(6) Wirtz, P. H., & von Känel, R. (2017). Psychological Stress, Inflammation, and Coronary Heart Disease. Current cardiology reports, 19(11), 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0919-x

Leave a comment